Getting Started

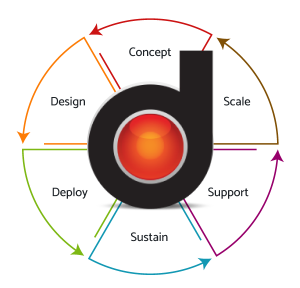

The DETECT service model is a wheel. We don’t stop after deployment. We’re here to help make sure your surveillance system is working, it’s delivering what you need from it, and it’s becoming an irreplaceable part of your workflows. And all that starts with a Concept.

The DETECT service model is a wheel. We don’t stop after deployment. We’re here to help make sure your surveillance system is working, it’s delivering what you need from it, and it’s becoming an irreplaceable part of your workflows. And all that starts with a Concept.

The next step is a phone call or a meeting where we learn about your situation, your requirements, your stakeholders. You tell us about your problems, history, and hopes for what a new surveillance system will achieve. And that’s the hardest step.

From there, DETECT can take the reins. We will audit any existing infrastructure and assets you have, look at the status and the users, and start to build a map of what your most effective system might look like. We work within your budget constraints, and offer very customizable options for payments, service, and support. We’re a team now.

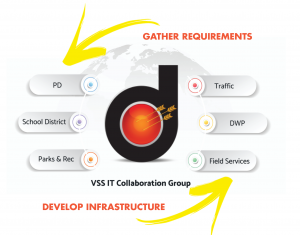

We often find that multiple independent surveillance systems are already deployed, but woefully underutilized. Developing an infrastructure for a municipal surveillance system should be a collaborative process led by a technology focused group that works with all the stakeholders to determine and fulfill current — and future — requirements.

We often find that multiple independent surveillance systems are already deployed, but woefully underutilized. Developing an infrastructure for a municipal surveillance system should be a collaborative process led by a technology focused group that works with all the stakeholders to determine and fulfill current — and future — requirements.

A successful surveillance system needs be designed with a solid foundation of the goals and metrics of the project. If the system is planned strategically, it can incorporate the existing assets and maximize the effectiveness of each agency’s independent surveillance system. At the same time, each department enjoys the benefits of reduced overall cost, more comprehensive coverage, and streamlined management and monitoring.